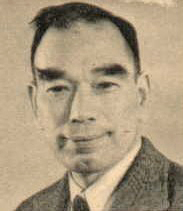

Jun Fujita, writer of tanka and photojournalist of 1919 Chicago Race Riot

| ||

chicago daily 34 massacre 1929. Jun Fujita, photographer. St. Valentine's Day

|

|

| haunting image taken by Chicago photojournalist, Jun Fujita, at the scene of the SS Eastland disaster. |

In my last post (link) I laid out the bare basic of some

poetic forms that can be adapted to writing flash—or at the least observing

nature and writing small about it. But as one can see from Eve Ewing’s poetry

collection 1919, yes her remarks emanated

from setting a scene or landscape but also were responding to the 1919 Chicago

Race Riot. And, also commenting on contemporary culture.

I was first introduced or given visual cues about the

Chicago Race Riot while visiting the Poetry Foundation. I forget what

event I was there for, but there is a small exhibit space that they use to

great impact. I’ve seen a few exhibits there that I’ve posted about.

The focus of the exhibit was a Japanese-born photographer

and poet, actually a Renaissance man as he was also an actor—but you get it,

anyway, the show was about Jun Fujita (1888-1963). He is responsible for the

most famous photos of the Eastland disaster, the Chicago race riots of 1919,

and the St. Valentine’s Day massacre, among others. He contributed to Poetry often in the 1920s. He also took

photos of camels at Indiana Dunes. From Wikipedia:

In addition to a historic career as a photojournalist,

Fujita was an accomplished and published poet and author. Fujita was the first

Japanese-American to write tanka, a form of waka. He compiled a collection of

his poems in Tanka: Poems in Exile. Fujita

worked as a silent film actor for Essanay Studios in Chicago, a movie studio

which was best known for producing several Charlie Chaplin comedies. Fujita had

several minor roles before starring in a lead role in the two-reel film called

Otherwise Bill Harrison in 1915.

Then this:

Fujita married Florence Carr, a white journalist from

Illinois. They could not legally marry until 1940 due to American laws against

“race mixing”. Florence was born Flossie Carr in Ringwood, Illinois on 16

October 1893 and died on Chestnut Street in Chicago in October 1974. The two lived

together at 1930 West Chicago Avenue in Chicago, Illinois and they had no

children. Fujita also owned a cabin in Minnesota, which was called "Jap

Island" by locals. Fujita's cabin is listed on the National Register of

Historic Places.

Fujita was granted honorary citizenship in the United

States by an act of Congress. The United States Senate Bill was submitted

by James Hamilton Lewis, who was the senator from Illinois at the time. Senator

Hamilton submitted the Bill for Fujita's American citizenship due to Fujita's

contributions to American society in the area of photojournalism. Fujita's

citizenship came at a time when Asian-Americans were not allowed American

citizenship by naturalization due to their race. After the attack on Pearl

Harbor, Fujita volunteered to serve in active duty for the United States but

was turned down due to his age, as he was 53 years old at the time.

Fujita died on 12 July 1963, at the age of 74. Fujita was

cremated and interred in an unknown plot in Chicago's Graceland Cemetery, most

likely in the Japanese section.

Thinking about this extraordinary man I can’t help but

wonder: a Japanese man taking photographs of black men getting stoned. Eve

Ewing’s book 1919 contain several

photos by Fujita. It seems he was one of only a few cameramen to risk life and

limb and enter the fray. Perhaps the only person. He directed his camera at all

aspects of the race riot. She has in the book a photo of ice being handed out

from a railcar after the riots to black residents. So he didn’t just point his

camera at “action” or blood shots but also at the more mundane. Because, in

fact, it is some of these more mundane elements that show inequality and

disparity. What the white population had come to expect of such as electricity,

hot water, flush toilets, etc was not always available in segregated black

households. In tenement housing. We see these patterns still today in Chicago.

The level of violence acceptable on the south side would get a mayor/alderman

fired on the north side.

Fields of Vision: Spirit & Place

Fujita was a master of tanka, a minimalist genre of

classical Japanese poetry. Some of what

he wrote at Rainy Lake, Minnesota, was published in book form in English in

1923 as Tanka: Poems in Exile. The poet

was deeply moved by glacial landscapes, sand dunes, and lakes, all of which he

found in abundance in the Upper Midwest.

He could find them close to Chicago itself. His earliest work from the North Woods shows

how, once he returned to urban life, he could find a sympathetic landscape in

the nearby Indiana Dunes:

Across the frozen marsh

The last bird has flown;

Save a few reeds

Nothing moves.

The air is still

And grasses are wet;

Thread-like rain

Screens the dunes.

Also from the above link: As Denis Garrison, who has

republished some of Fujita’s work, writes:

“The reader cannot help wondering if the things he saw as a photographer

influenced Fujita as a poet, and likewise, if the way he understood poetry

informed his photography.” He writes

about “death-like” expanses of snow, of snowdrifts where “thin fangs dart.”

What is tanka?

“Tanka are notable for their accessibility,” Garrison

explains. “Why? Because most good tanka have ‘dreaming

room.’ They have been composed with the

technique of understatement, of suggestiveness . . .

I like this=dreaming rooms. This is a space I could inhabit.

|

| Jun Fujita |

Comments